British Buses: The Loss of a National Asset

https://www.humantruth.info/british_buses.html

By Vexen Crabtree 2021

In England and Wales, buses were privatised and deregulated in the 1980s1.Since then, the UK government - largely the Conservative Party - have systematically defunded services under the policy of commercialisation, having the effect of continually reducing the number of routes and the frequency of buses2 except in cities3. Remaining council-supported routes have been steadily defunded3; between 2010 and 2018 alone they lost 50% of their funding2,1. Bus Fares have risen and priced out commuters and individual travellers3. The result, according to the Campaign for Better Transport, is that "we are... seeing the emergence of `transport deserts´, with limited or no transport apart from individual cars"4 and unable to be a part of ordinary life planning. It's not only passengers and communities that suffer - bus drivers are paid just a scrape above the UK's National Living Wage and as a result, the industry has a growing shortage of drivers5. Despite the neglect, the benefits of buses are clear6 and the abandonment of them is causing long-term pain and damaging the status of the UK as a developed country.

- The Benefits of Buses

- The Failure of the Commercial Model

- Exceptions

- The Fuel Crisis of 2021

- The Collapse of Local Authority Funding for Buses 2010-2018

- The Long Term Policy

- Conservative MP Michelle Donelan: Solve the Problem With More Commercialism

- Links

1. The Benefits of Buses

Buses have better fuel consumption and lower noxious emissions per passenger, and reduce road congestion.7,4,8,9. Buses are especially important for those on low incomes1,9. Buses provide an important and adaptable link between residents and fixed train stations, preventing the need for extensive and voluminous car parking solutions at stations, and linking together parts of the transport network. Short-distance park and ride schemes have been instrumental in alleviating entire cities' issues with clogged cars. It is important to have alternative modes of transport than personal cars - if buses are better, people panic less about petrol (helping to keep prices down) and more people can get to work and training.

For more, see:

Greener Journeys' data shows that "every £1 invested in local bus infrastructure brings more than £8 in wider economic benefits"8.

“[The decline in buses] affects everyone, but especially people on low incomes, the young and the elderly. Without immediate action to halt the decline of Britain´s buses, many could be left without a way to access vital services and opportunities - and ultimately, excluded from society. [...]

Children under 16 account for 19% [of bus passengers], and those aged over 60 account for 25%. [...] England´s lowest income people also make 75% of their public transport trips by bus. [...]

But even those households with a car or van suffer from poor public transport options: around 9% of all UK households have a low income but high motoring costs. Without good public transport, these households have no option but to find savings elsewhere, to meet the cost of driving.”

Nicole Badstuber (2018)1

It's not the case the buses must only support the poor; in some affluent places such as Bath, bus patronage is increasing in sync with upwards growth in personal wealth3.

2. The Failure of the Commercial Model

In England and Wales, buses were privatised and deregulated in the 1980s1. The commercial model sees profitable bus routes sold to commercial operators, with others being supported services ran with top-up funding from local transport authorities3. Services are supported if they are commercially unprofitable but local councils deem them essential for the local community3. However, central government does not give clear protection for bus funding, so that when hurtful cuts must be made, money can be pulled from bus funding rather than mandated services3.

Ticket prices have risen relentlessly3 and services have been steadily cut3. So, buses are too expensive and too sparse to be a sensible part of life-planning for many, so patronage is falling. This reduces revenue, which makes commercial operators cut more services, and, makes local authorities tempted to reduce funding even more. It is a never-ending cycle of decline3 which will continue as long as central government does not mandate service levels or stovepipe bus funding.

Over the past 20 years, the distances travelled by buses on their routes has reduced almost 1% each year1. Conversely, on commercially profitable routes where companies have a vested interested in keepings things running well, bus-miles has increased by 1.8%1. Provision is skewing squarely to where money can be made, rather than to where buses are needed/ This short-sighted policy has the result of creating an ever-shrinking sphere of mobility for buses and onwards journeys, resulting in diminishing practicalities of planning journeys by bus.

“Bus travel per head is declining throughout Great Britain, even though, overall, people are travelling more. [...] Local authority-supported services outside London have halved in vehicle mileage since 2009. [...]

Perhaps it is also time for some bold experiments, like that in Dunkirk, which has reduced bus fares to zero!”

"The vanishing bus rider: What are the reasons for the great decline in bus ridership in the UK?" by Michael Waterson (2019)3

In an era where we ought to be using every method possible to encourage reduction in combustion emissions, the cost of travelling by bus has gone up compared to motor cars - "whilst the consumer price index (CPI) has risen 22 percent since the start of 2009, bus fares have risen on average by 39 percent"3.

“[T]he Government ignoring buses is a mistake. [...] . It stops people getting access to training and jobs. [...] . It makes it more difficult for people to get to health services, especially more specialist services in hospitals. So cuts in bus services add to poverty and social exclusion, and to isolation and loneliness - research we commissioned in 2012 in two communities in South Hampshire and Teesside which had lost all or most of their bus services showed this effect strongly. [...] We are therefore seeing the emergence of `transport deserts´, with limited or no transport apart from individual cars. [...]

The new Bus Services Act does offer some help [...], but more is needed. Joining up transport funding across different departments will help - and, ultimately, it needs the Governments in England and Wales to take buses as seriously as other transport modes, and recognise their wider value.”

"Buses in Crisis" by Campaign for Better Transport (2019)4

“[Now, f]or many people, particularly those living in rural or remote areas, bus and train services are few and far between - if indeed they exist at all. Even if you are lucky enough to live in a place which does enjoy some kind of coverage, timetables and the availability of connections can often make it hard, if not impossible, to use them. Of course it is sometimes possible to overcome these difficulties by adopting our own sort of hybrid, personal approach to integrated transport, shifting from bicycle to bus or from car to train for different parts of the journey [but] this rather begs the original question regarding public transport itself.”

"Is Public Transport Always Best?" by Dr Gareth Evans (2021)9

The neglect of bus funding and the reduction of services to keep routes profitable isn't just an issue for customers. Bus drivers themselves face problems; their wage is only just above the UK's National Living Wage of £8.91/hour10. When unions threatened to strike over this issue in 2021, the large operator Stagecoach said it simply couldn't afford to pay its drivers more than £9.25/hour5. After a string of accidents resulting from over-worked and stressed drivers, this can hardly be helping the state of the UK's bus system. The entire industry is in need of a radical rethink; primarily, this means the Government ought to be upping the priority of the bus service, and downing the priority of the well-looked-after (and rich) personal car industry. They'll find that helping out buses actually reduces the overall national cost of transport.

3. Exceptions

In London, things are different3. Bus use there remains high3.

“Over the last 25 years, bus usage per person has increased by 52% in London, while falling by 40% in England´s other metropolitan areas. More than half of all bus trips in England now happen in London. London has, to some extent, managed to buck the long-term downward trend, because unlike in the rest of England, the bus market there was not deregulated.

London retained its ability to strategically plan and manage the routes, frequency, times of operation and fares of its buses. Its model means that profitable routes can cross-subsidise less profitable - but socially important - routes. What´s more, having control of the bus network means all the different modes of public transport can be organised to deliver better travel options to all, and a viable alternative to the car.”

Nicole Badstuber (2018)1

The places outside London where bus use is strongest is in Brighton and Hove, Nottingham, and Reading3. Of these, in Nottingham and Reading, local authorities still provide most of the bus services3, which in general is a more successful scheme than the commercialist model that has been in place since the 1980s - Reading is seeing steady increase in bus use.

4. The Fuel Crisis of 2021

The UK fuel crisis of 2021 reminded Brits just how valuable it is to have alternative modes of transport available. Panic-buying of petrol turned a manageable supply issue into a national crisis that saw emergency vehicles competing with civilians for fuel over a period of multiple weeks, with a large portion of petrol stations closed or on intermittent stock. If the national bus system was comprehensive and there was still a culture of bus use, people would have switched. But the long-term defunding of buses under the commercialist model meant that where the buses were needed the most - urban areas - they are in the shortest supply.

5. The Collapse of Local Authority Funding for Buses 2010-2018

Source:11

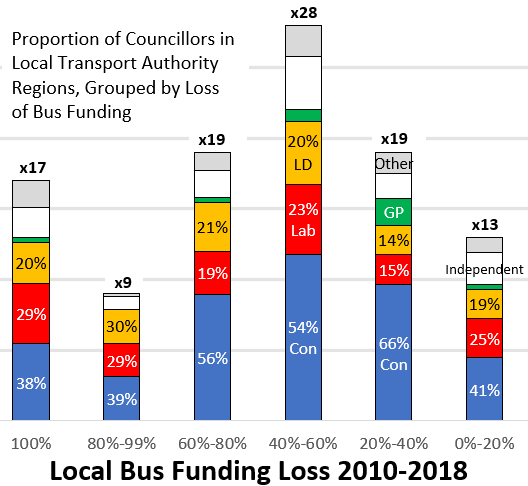

In almost every region across the board there has been a drastic reduction in funding for local bus services. From 2010, total funding has been reduced by 50%2,1. Seventeen areas have lost all funding2; only a very few have avoided losses. No political party has managed to resist the push from the central Conservative government to replace taxpayer funding with commercial funding of routes, The result is that since 2010 in England and Wales, 3347 bus services have been ceased or reduced1.

Here's an example of how to read from this chart: Local Bus Funding was reduced by 60 to 80 per cent in 19 local transport authorities, and in those areas the local councillors responsible were 56% Conservative, 21% Liberal Democrat and 19% Labour .

"Buses in Crisis" by Campaign for Better Transport (2019)2 says that the funding losses have taken three forms:

- "Bus Service Operators Grant, which goes to all bus operators was cut by 20% in 2012-13, and has not increased since.

- Funding for local authorities has been cut in general, and this has fed through to cuts in support for bus services, which have less legal protection than other local authority services.

- The free travel scheme for pensioners and the disabled is underfunded by the Government, meaning that operators are having to carry people for free without proper funding to reflect the cost of this.

6. The Long Term Policy

The Conservatives' current instincts towards buses aren't new; Margaret Thatcher is often credited with saying that anyone over the age of 26 who uses buses "can count himself as a failure". This inability to imagine how the lives of others might differ from your own - a lack of basic human empathy - has been a severe hindrance in the long-term development of a good strategy for funding public services such as unprofitable local bus routes.

Central government gives bus services less legal protection than other council services, so that when overall council funding is cut, bus services are also reduced.2. It's the council-funded ones that are of most critical value, because they're the unprofitable routes serving the most remote and spare users, who are also not served by the rail network. Yet, it's these exact services that have the least support from central government, who exclusively favours the commercially successful routes to the extent that even the new Bus Services Act (2017) still ties bus funding to commercial contracts, as does a 2021 bus funding push.

7. Conservative MP Michelle Donelan: Solve the Problem With More Commercialism

In the midst of the failure of the commercial model, the Conservative MP Michelle Donelan wrote to her fellow, the Secretary of State for Transport, mentioning that Wiltshire, like other areas, are feeling the squeeze on public services, and pointing out that "subsidised bus services are not a statutory service, but are used when it is not economically viable for a commercial operator to run a local service that councils believe are needed".

She notes that "a significant number of my constituents have raised concerns" about the loss of services, in particular about the impact on the elderly and disabled residents. It seems that she hears the problems: local councils don't have enough money to maintain the services, and it is impacting on people's lives.

But her solution is not less of the hands-off Conservatism that got us into this mess, but rather for more corporate involvement and the removal of public funds altogether:

“I strongly believe that the future of Wiltshire´s bus service would be greatly enhanced by the ability to adopt an enhanced partnership across the county. An enhanced partnership will help ensure that all services are operated by commercial companies, with no subsidy from taxpayers, but the contracts are to run specific services as set out by a Local Transport Board, which would bring together the councils, residents associations and industry experts.”

Michelle Donelan, Conservative MP (2016)12

It's hard to really see what's going on, because aside from some positive-thinking about the commercialist model, her letter doesn't include any factual breakdowns of which companies would want to pay into loss-making services, nor, which of those services in particular would be cut as a result of the complete removal of taxpayer money. Her instinct, fed by the Conservative approach to services in general, was that the solution should be the reduction of public funding.

But I'm not sure at all that Michelle Donelan knew what was coming in terms of government action, because in 2021, the Government had relented and promised to restore £3bn of the funding of public bus services13, under the guide of the Enhanced Partnerships that sees the money go to commercial operators as long as they promise to improve services in accordance with a locally agreed plan14. The strategy states "there can be no return to a situation where services are planned on a purely commercial basis"15. To keep to her word in her letter, she'd have to reject any of that money, but, the funding is required because the commercial model of bus services doesn't work, except on some routes in cities are large towns.